The Alignment

With such a tight deadline, engineers had to think fast, and creatively. Conventionally, when an alignment needs to be worked out, you require several jeeps, and lots of people running around. Mr. Rajaram, who was then the Chief Engineer at Goa and later went on to become the Managing Director of KRCL, took satellite images, made topographical maps with high accuracy, and then — for the first time in the history of the Railways — sent out teams on motor cycles. He ordered several Kawasaki bikes, modified to carry equipment.

like levelling instruments and hired young boys, fresh with their engineering diplomas, to go around the state.They were given Rs. 100 per day, and petrol,neither of which they had to account for, so long as they produced a certain amount of work every day, of course the targets they were set meant they would have to work 14 hours a day. But they felt empowered, and so they gave their best. It helped that despite their inexperience, they were given the designation of `Engineer’, a title they could flaunt with pride.

like levelling instruments and hired young boys, fresh with their engineering diplomas, to go around the state.They were given Rs. 100 per day, and petrol,neither of which they had to account for, so long as they produced a certain amount of work every day, of course the targets they were set meant they would have to work 14 hours a day. But they felt empowered, and so they gave their best. It helped that despite their inexperience, they were given the designation of `Engineer’, a title they could flaunt with pride.

Thirty such teams in Goa worked on 16 different alignments, and the data was analysed, often way past midnight, on an assembled computer that Mr. Rajaram bought cheap in Bangalore. Mr. Rajaram designed the software for this analysis himself. This approach meant that survey work was done at 10 per cent of the cost that it would have normally involved.

While the alignment was being finalized in Goa, hectic activity was going on all along the Konkan. The first working season between 1990 and 1991 was utilized for a detailed survey, pegging out the route on the ground, preparing land plans, drawings and tender schedules, conducting investigations on the soil, deciding at which point exactly a bridge had to be constructed, or a tunnel bored. During this intense period, KRCL succeeded in reducing operational benefit to the Railway system.

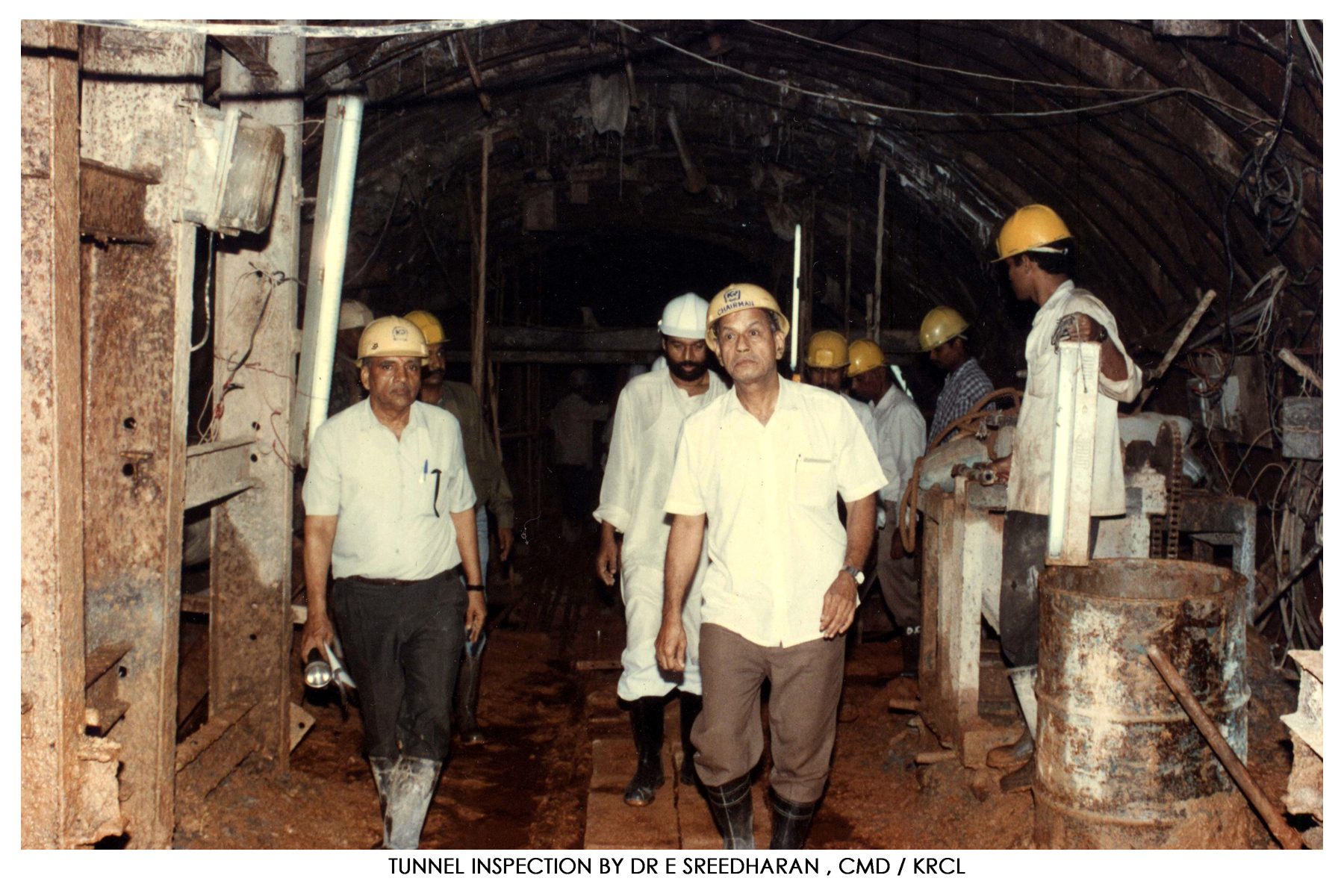

The achievement was made possible by the fact that several senior officials, including Mr. Sreedharan, Mr. S.V. Salelkar – then Engineer-in-Chief (Projects), and Mr. A.K. Somanathan – then Engineer-in-Chief (Technical), walked down the entire route, along with the sectorial Chief Engineers. It was not easy, climbing up and down all those hills and valleys.

A detailed environmental impact assessment study (EIAS) of the alignment was carried out in two phases through Rail India Technical and Economic Services Ltd. (RITES), a public sector undertaking under the Ministry of Railways. Under Phase I, stretches between Udupi and Mangalore were covered. Under Phase II, the study was conducted between Veer and Sawantwadi. RITES conducted a separate EIA study for the balance alignment in Goa. The Goa government approved the alignment, which was finalized in December 1990 after detailed discussions with state authorities. In March 1991, the new government again confirmed the alignment.

A detailed environmental impact assessment study (EIAS) of the alignment was carried out in two phases through Rail India Technical and Economic Services Ltd. (RITES), a public sector undertaking under the Ministry of Railways. Under Phase I, stretches between Udupi and Mangalore were covered. Under Phase II, the study was conducted between Veer and Sawantwadi. RITES conducted a separate EIA study for the balance alignment in Goa. The Goa government approved the alignment, which was finalized in December 1990 after detailed discussions with state authorities. In March 1991, the new government again confirmed the alignment.

While working out the plans, many factors were considered, like optimization of earthwork, tunnels and bridges, and the least interference to habituated areas; the minimum damage to horticultural lands, especially mango and cashew groves; and avoiding reserves and thick forests, while at the same time achieving the goals of flatter gradients and curvatures. In Goa, where people were particularly emotional about having to give up ancestral property, KRCL engineers personally visited each house to see if there was any way it could be saved. In many cases, a way out could be found. That’s why Goa has the maximum number of curves on the alignment. Even the Mandovi bridge is on a curve. As a result of this careful appraisal, only 35 houses were disturbed in Goa, where the population density was highest. And faced with the pressure from local residents, the Konkan Railway team found their engineering skills sharpened.

During this process, some difficult decisions had to be made. Near Dasgaon, at the confluence of the Savitri, Kal and Nageshwari rivers, was a burial ground, exactly on the Railway alignment between Dasgaon Tunnel (South face) and Savitri bridge. There was no way that the alignment could avoid this route, so Konkan Railway built another cremation ground for the villagers with a wide approach road, transplanting bones to the new location after conducting appropriate rites. Shifting of this burial ground was a formidable task for engineers. It was achieved skillfully by persuading each individual of Dasgaon village and involving local leaders and the MLA.

But the spirits, apparently, had something to say about being disturbed; engineers reported that a heavy cement mixing machine that was lying on the old burial ground, had mysteriously been turned around at night!